You're a Bad Liar: A Response to 'Dead Man's Letters'

You’re a bad liar.

You may think otherwise at times when speaking to someone who wants to believe you. Someone whose worldview, or even their counterview, is galvanised by your tantalising deceit.

They may revel in the opportunity to dance with another actor through this theatre performance. Locked in step, screaming, cursing, loving, and caring for one another. Your lies bring great relief to those around you.

But you’re a bad liar. A good lie is measured by how well a nontruth becomes reality. So, it must be measured against those who have no reason to believe you and no desire to know a nontruth.

There are few in this world that you can confidently measure lies against.

Poets are a sure bet. They are absolutely content with being observers of the world. So to see cardboard cut-outs where behind stands a perfectly good brick wall, they have no interest. No matter how grand the theatrics are, they are still false.

Those that rely on their hands for work and to make a living hold a similar indifference. They understand the world through what they can touch. However, they may not have the toolset of a poet to decipher a lie's purpose or bring about it’s deconstruction. Nonetheless, they will understand its falsehood, one that is made by self-proclaimed ‘clever people’ living in fantasy worlds.

But the true test of a lie is to tell it to a child.

We often look to children as beacons of innocence and, against our best interests, ignorance. Believing that they can’t possibly understand the world and have yet to learn their place in it.

Our error may be illustrated by the example of following in the footsteps of previous generations. That path is one of desire or convenience, where grass has been pushed aside over time by falling feet. Foolishly, we might assume it was formed with intention.

We see it as the way things are.

A child understands; that’s the way things have been, and a new path is as easily taken.

Children have the blessings of both the poets and the workers. From the latter, the world is physical, ruled by what you can touch. A child has aspirations, possibly, but ones so lofty that they remain delightedly disconnected from any business or celebrity intentions.

And like a poet, they see the world in front of their eyes for what it is. They may imagine incredible visions beyond it, but still, these are firmly connected to what they see and hear. New information about the world is discovered and gleefully accepted.

There is no better demonstration of a child's ability to see the truth than, unfortunately, in war.

…

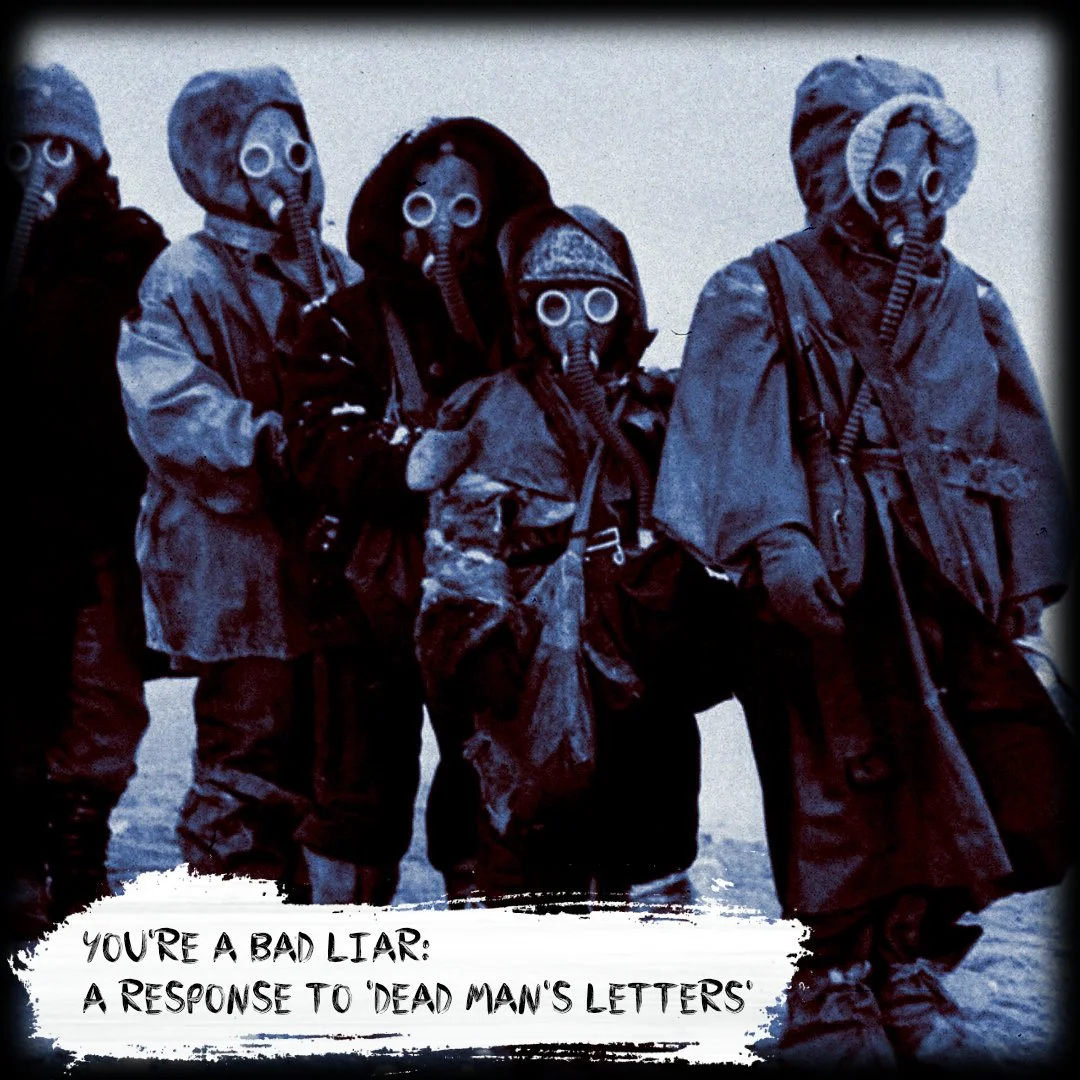

This topic came to mind while recently watching the film ‘Dead Man’s Letters’. A 1986 Soviet post-apocalyptic drama directed by Konstantin Lopushansky. You can watch it for free (along with another few films of similar topics) here: http://exmilitai.re/film.html

I’ve always been fascinated by post-apocalyptic themes. Starting with my discovery of the 90’s video games Fallout 1 and 2, and then later watching movies like Mad Max.

Part of my attraction is the sense of discovery, action, adventure, and the imagery itself. Bleak monochromatic landscapes that are utterly human yet completely otherworldly.

But the reason I believe I have an obsession with post-apocalyptic material is the dark comedy of it. The beautiful truth of it all.

Humanity, with all its hubris, has brought about it’s own destruction in the most utterly stupid ways. Ignoring climate change, creating super bugs, or, of course, through nuclear annihilation.

All preventable, all foreseen, yet perhaps all inevitable.

‘Dead Man’s Letters’ addresses these topics through fantastic monologues and conversations. I won’t spoil anything here; this isn’t a review or deep analysis of the film. But one image has stuck in my mind.

The blank, disappointed faces of the children. Not despair, not fear, not stubbornness—though these are present at times. Disappointment is the palette they paint us in.

In the place of innocence on their faces, I see deep understanding beyond the facts or history of the situation. They see the sad truth in everything.

Knowing how things came about—numbers, dates—is all very important. We should all endeavour to get our facts straight, call things for what they are, and strive for complete knowledge of whatever we believe we know.

But a child doesn’t need that to see truth.

The children in ‘Dead Man’s Letters’ are silent, watching us, knowing what we have done. The world around them is dark, terrible, and hostile. Echoes of past worlds sit crumbling on top of one another. Adults shout, attack, and despair in this world.

The world as it is.

But to the child, looking to the only ones who could have played any role in the current state of affairs, see the world as it has been. Fools at the helm. Self-consumed and idiotic. Liars.

Bad liars.

…

‘Kids these days.’ One of the stupidest possible ways to start a phrase still rings out across dining tables, TV screens, and on our phones. I don’t believe it will ever stop, of course, and neither should young people go utterly unchecked by anyone older than them. There is a deep wisdom in age, but there is also apathy.

We are tired, and I’m sure you feel it. Tired of seeing the truth of it all and understanding how utterly insane so many of the lies controlling this world are. I’m not speaking of conspiracy theories like dark cabals, but simply the lies we tell ourselves that are all a rephrasing of ‘That’s the way the world is”.

In a time where information flows more freely and from more sources than ever before, the truth is perhaps harder to see. However, our reaction cannot be to turn to the comforting lies of others and of ourselves so that we may rest our eyes, our ears, and our hearts.

You’re still a child. While we huddle in nuclear bunkers, the children staring back at us with disappointment still have the strength to see truth - strength you once had.

…

This film is amazing, and it tackles many more themes throughout its runtime about the nature of humanity at the end of history. It’s a dark, all-too-realistic, fascinating watch.

I highly recommend you check it out; it’s free and has a run time of only 90 minutes.

I’m being hyperbolic with my expansion of this theme for dramatic sake, but at it’s core, I do believe in this simple message. Truth is, in some capacity, subjective. Reality is in our heads. We are trapped in a brain that can only translate what we see, hear, and feel.

But I do believe that most of us see truth. Not facts about the world, but a direction forward that is honest and just. I hope we can all find the strength to follow it.

Or, at the very least, we know when someone is lying. We’re all terrible liars.

-Rhath

Also, if you like what I do, you can throw me a couple bucks on Patreon

but mainly just follow me on Instagram